Interview No.63 Hauska Eduard

環境・社会理工学院

Introduction

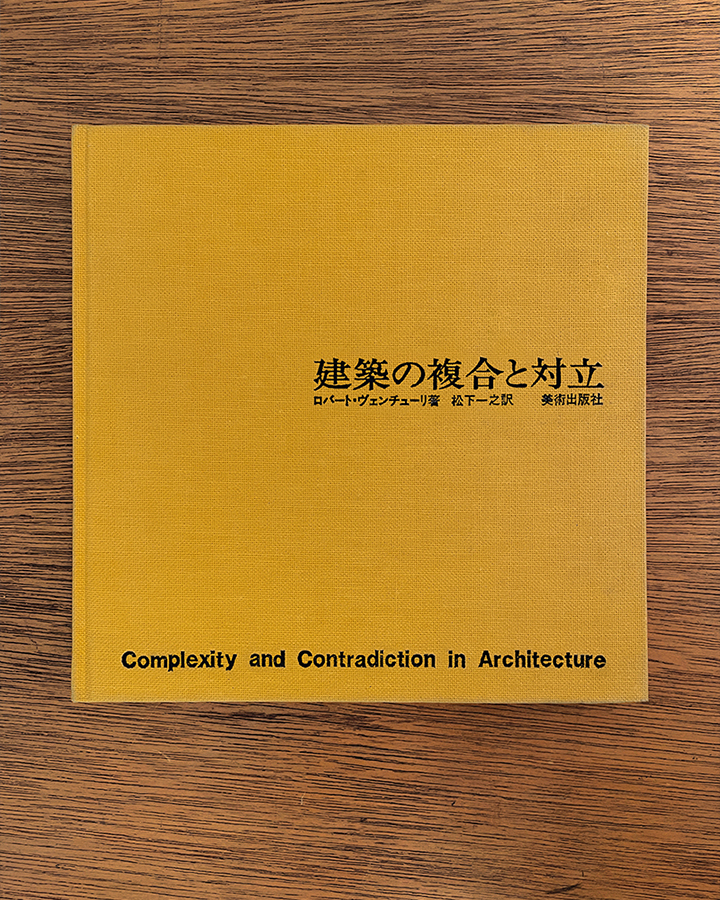

I am a PhD student from Sweden with a background in architecture. I received my bachelor’s degree from KTH Royal Institute of Technology in Stockholm and first came to Japan in 2019 as an ACAP exchange student at Tokyo Institute of Technology. During that half-year stay, I became increasingly interested in my professor’s research on how architects use language and theory to describe complex ideas in their work, and by the end of my exchange period, and through the realization that every project description carries ideas that reflect broader cultural, philosophical, and disciplinary shifts, I decided to remain in Japan and apply to the IGP International Graduate Program. Under the inspiring supervision of my professor, I developed the idea for my master’s thesis titled Conceptions of Complexity in Architecture drawing on a foundational theoretical work by Robert Venturi, the father of architectural Postmodernism, that speaks to every architect concerned with thinking architecture, not simply designing it.

As my research progressed, it became clear that the theme was far too vast to be fully covered within the framework of a master’s thesis alone, and that realization laid the foundation for my transition into the doctoral course, and a decision to stay on at Tokyo Tech (now Science Tokyo), driven not only by the relevance of my research theme and the expertise of my academic supervisor, but also by the institute’s reputation for fostering architectural discourse and supporting both creative and critical thinking. In addition, Tokyo itself, a city of intertwining and colliding layers, infrastructural marvels, and architectural artifacts spanning different styles and historical periods, continues to serve as a daily source of inspiration for my research.

研究概要 / Research Outline

Research Summary

In architectural discourse, complexity has long been an essential term, notably introduced by Robert Venturi’s seminal 1966 book Complexity and Contradiction in Architecture. While Venturi’s work marked a foundational moment architectural theory, the term has gained renewed significance in recent decades, no longer simply a reaction to Modernist purism, but rather a guiding concept in contemporary design across a wide range of projects, from socio-ecological urbanism to extravagant formal expressions. My research investigates how conceptions of architectural complexity have evolved since 1966, specifically how architects and critics articulate complexity through their project descriptions in internationally renowned architectural magazines.

For my analysis, I have collected over 200 project essays spanning nearly six decades and covering a wide range of international architects and design cultures. To examine this mastodon of material, I adopted the well-known Japanese KJ Method, developed in the 1960s by ethnographer and former Tokyo Tech professor Kawakita Jiro as an alternative to Western quantitative approaches. My supervisor, Shin-ichi Okuyama, introduced this method into architectural research in the 1990s, and I have adapted it to categorize and analyze how the notion of complexity has been described and framed in contemporary architectural discourse, aiming to reveal not only how architecture is conceived but also how it is communicated, interpreted, and positioned within the broader intellectual context.

Focusing on texts has allowed me to engage with the epistemological side of architecture, not just on physical built form, but on the ideas, language, and theories behind buildings. I believe these narratives are crucial for understanding contemporary architecture culture, especially as it becomes increasingly globalized and interdisciplinary, and my aim is to contribute to ongoing debates in architectural theory by offering a critical perspective on how complexity functions as both an idea and a design tool.

Complexity and Contradiction of Doctoral Research in Architecture

Routine

My daily research routine involves a combination of material collection and structuring, filtration and analytical reading of the said material, and writing, rewriting, and writing everything again. Fast-forward on repeat. Since my work is mostly theoretical and does not require laboratory work in its traditional sense, it demands a different kind of discipline: long hours of close reading, sometimes of material that turns out to be nearly useless (or so it seems), re-reading, categorizing, and critically reflecting on the results. Here, the conviction in your research theme becomes important, and maybe more important still is your endurance. I once read somewhere that the percentage of unfinished PhDs is quite high, and that those who reach the finishing line may not be the brightest, but the ones who believed in their idea the strongest and stuck with it through all the downfalls and methodological issues, which guaranteed will happen! The stubborn ones who kept pushing, and who, even after several years, could still stay enthusiastic about their theme, and, very importantly, explain it comprehensively and with excitement to others, those are the ones who might hold the precious degree certificate in their hands at the end.

I am still in the process of finalizing my research, but I can already say that partially that statement is true. We have to constantly keep ourselves motivated, and without the strongest passion for both the discipline and the chosen research theme (you brought it upon yourself, nobody forced you, says my inner me), there can be no positive outcome. In my case, it was an interest born already during my bachelor’s studies, which I developed into a coherent theme during my master’s, and now have the opportunity, thanks to the Institute of Science Tokyo and the SPRING Program, to develop into a full-fledged theory. I am convinced this work will help the next generation of architects to better comprehend essential aspects of architectural design theory and practice, so I keep doing my part and reinvent the original concept I had long ago over and over again.

Another essential ingredient is probably the right supervisor. Meetings and discussions with this very important person will be frequent, and sometimes quite long. The respect for, and an interest in, the research and expertise of your supervisor cannot be overstated. This relationship must be nurtured carefully, and the supervisor chosen accordingly. A lot of your “bright ideas” and critical perspectives on the theme will come from your professor, peers, and the lab. We must stay convicted of our own path, but flexible enough to think outside of the box and from various perspectives, and sometimes “kill our darlings,” in order to make a step forward.

Finally, when it comes to planning, which of course, very much varies from person to person, I can say that some people rely on schedules and try to stick to them neatly, but that has never really worked for me. I usually sit down and work in long stretches, sometimes overnight, if I feel the work is flowing well. When I reach my limit, often when the task is finally done, I will take a long-awaited and well-deserved break. This might not work for everyone. Some people cannot function properly without their daily walk in the park (whatever!) or at least one free weekend day. But personally, I cannot fully relax when a deadline is ringing in the back of my mind and put full 200% of my attention into that one urgent and important task, pushing all the distractions (essentially the rest of the life) on hold until the job is done. “Work hard and play hard,” as some say! But this is something each of us must figure out on our own, and perhaps, if you are considering joining our PhD crusade (it is actually incredibly exciting!), or if you are already in the process, you probably know what kind of schedule and working rhythm suits you best.

メッセージ / Message

Final Message

There are, perhaps, too many reflections I would like to mention here, so I will try to be brief.

Firstly, doing a PhD is a personal challenge, and an intellectual one at that. At times, the work feels solitary, and there are days when your batteries are drained to the bottom, when there is simply no willpower left to fight off procrastination. At those times, remember that the purpose of it all lies in the path itself. We are improving, although it might be hard to notice right away. The progress is a gradual thing and often becomes visible first much later. It is worth acknowledging even a single line added to your manuscript. And if that is what it takes, sit down and stare at the empty Word document for half an hour. The appetite comes while the food is being served, you know! Work at your own pace and let your own consciousness be the final quality check. It usually does not lie. For anyone considering the research path, I would say this: choose your theme wisely, after all you will dream about it, wake up with it, and live with it for a couple of years, perhaps even for the rest of your life.

Secondly, be grateful. Be grateful for the opportunity to do the research. Be grateful for the comments, even the harsh and critical ones, they might help you on the way improving your work significantly. Be grateful for being part of the Science Tokyo community with all the resources and connections it provides. Whether or not the final outcome matches our expectations, the knowledge gained along the way will remain valuable for any future path, whether within academia or beyond it. The very act of believing in yourself and your project, developing it from scratch, seeing it evolve and pushing forward against all the odds is in itself deeply meaningful.

And finally, the advice I wish I had heard at the beginning: take the time to build a network. Discuss with people beyond your immediate surroundings, those whose views are similar to yours, close enough to yours, or even entirely opposite, as long as they interest you (or try to understand why they interest others). These exchanges may sometimes seem distracting or diverting from your ultimate goal, but again, the research is rarely, if ever, a straight line. We move in circles, and returning to a good old idea with a fresh mind can be exactly what is needed. Embrace the unexpected and seize the opportunity, your next great idea might come from the narrow gaps between the obvious, or even from something that first appears dull and unattractive.